Imagine this: It’s 2026, and Phil Lynott steps onto a sold-out stage at Dublin’s 3Arena, his bass slung low, that signature swagger intact at age 76. Bono joins him for a blistering duet on a new track blending U2’s anthemic edge with Thin Lizzy’s street-smart rock. Later, Bon Jovi crashes the afterparty, toasting to their latest collaboration—a stadium anthem that’s topping charts worldwide. Lynott, the Irish poet of rock, laughs that deep, charismatic laugh, his eyes sharp, his demons long conquered. But this is just a “what if.” The reality? Forty years ago, on January 4, 1986, the world lost one of rock’s most magnetic frontmen after a harrowing 12-month battle against addiction, missed chances, and a body pushed to its limits. This is the story of Phil Lynott’s final year—a tale of raw talent clashing with self-destruction, told through the voices of those who knew him best. It’s a reminder that even legends can fade, but their fire never truly dies.

Philip Parris Lynott was born on August 20, 1949, in West Bromwich, England, to an Irish mother and a Guyanese father who left early. Raised in Dublin by his grandmother, Phil grew up tough, charismatic, and obsessed with music. By the late 1960s, he was fronting Skid Row, then formed Thin Lizzy in 1969 with drummer Brian Downey and guitarist Eric Bell. The band started slow, but hits like “Whiskey in the Jar” in 1972 put them on the map. Lynott’s lyrics—poetic tales of outlaws, lovers, and Dublin streets—set them apart. He wasn’t just a singer; he was a storyteller, blending hard rock with Celtic soul.

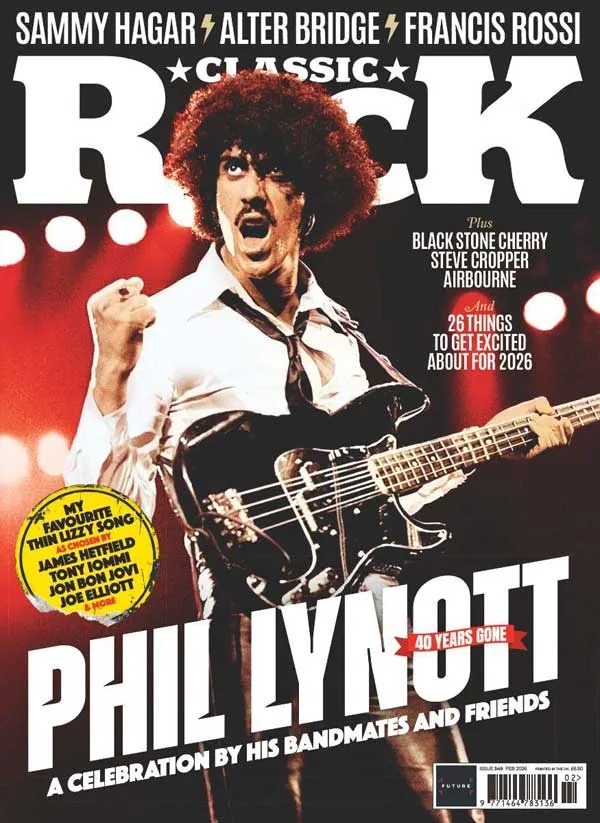

(Image credit: Future)

Thin Lizzy’s golden era came in the mid-1970s. Albums like Jailbreak (1976) exploded with “The Boys Are Back in Town,” a song that captured the essence of camaraderie and rebellion. Lynott, with his Afro, leather pants, and mirror bass, became an icon. Tours with Queen, Aerosmith, and Rush followed, but success brought shadows. Drugs crept in—cocaine for the highs, heroin for the lows. Bandmate Scott Gorham later recalled, “I came to the conclusion that I gotta stop taking this shit. It took me over a year after leaving the band to get it through my thick-ass fucking skull that this shit was going to kill me or ruin my career.” Gorham quit heroin via Dr. Meg Patterson’s treatment, but Lynott couldn’t shake it. By 1983, Thin Lizzy was fracturing. Their final gig at Nuremberg’s Monsters of Rock in September 1984 marked the end. Lynott, at 35, was adrift but determined.

Enter 1985: the year Lynott fought to rebuild. Fresh off Thin Lizzy’s demise, he formed Grand Slam, vowing a new chapter. “Basically, Phil said that he wanted to do something new with two guitarists, fresh with new blood, write new songs, sell it as a whole new band and not as a solo project,” recalled guitarist Laurence Archer, who joined after idolizing Lynott since age 17. The lineup included Downey, guitarist John Sykes, keyboardist Mark Stanway, and bassist Doish Nagle. They kicked off with a Scandinavian folk park tour in January, mixing Thin Lizzy classics like “Sarah” with new tracks such as “Military Man” and “Sisters of Mercy.” Gigs grew from small clubs to theaters, and Lynott seemed invigorated. Stanway noted, “After about seven or eight gigs, Phil was so happy with the way it went that he said, ‘We gotta keep this together.'”

But cracks appeared early. Sykes bolted for Whitesnake after an offer from David Coverdale, and Downey quit, exhausted by the “shenanigans.” Replacements Robbie Brennan on drums and Archer on guitar kept things moving, but drugs loomed large. Lynott’s heroin use caused mood swings—”He blew a bit hot and cold,” Archer said. “Some days he’d be easy and some days he’d be difficult and when he was he would come and apologise afterwards.” Heroin was a “swear word” to Stanway, who threatened to tell Lynott’s mother if he saw it. Yet, signs were everywhere: vomiting before gigs, asthma attacks from the smack. “Whenever he did the smack, he would get these asthma attacks, so consequently he was sucking on those inhalers all the time,” Gorham observed during a visit to Lynott’s Kew home.

Career hurdles piled up. Managers Chris Morrison and John Salter shopped demos to labels like Polydor, Phonogram, and EMI, seeking a £100k deal. Rejections stung—Lynott’s “wild man” reputation preceded him. “We were turned down by just about every record company there was,” Salter said. Drug busts didn’t help: In mid-1985, police tailed the tour after a West End party raid (Lynott escaped charges). He faced Irish courts for cannabis, heroin, and methadone possession—charges dropped, but warnings loomed. A Kew bust uncovered a cannabis plant and cocaine; another incident in a cab saw roadie Big Charlie take the fall. These led to visa denials for the US, scuttling sessions. Lynott lost his passport five times in three years, delaying everything. “Phil kept getting busted so I couldn’t get visas!” Salter lamented.

Personal life unraveled too. Lynott’s Kew home was a party hub with hangers-on fueling the chaos. His marriage to Caroline Crowther was strained—she’d later rush to his side in crisis. Court appearances painted a man on the edge: Barristers warned of jail time, leaving him terrified. “When we got to the court, she said, ‘This could be six months, you’re in it this time.’ He was terrified when he stood in that box,” Salter recalled. Yet, Lynott masked it all with charm. He did charity work, noted in court, and tried clean-ups. “There were occasions where Phil sat down with me and told me that he really wanted to knock it on the head, doing drugs and stuff,” Archer said. “He was trying very hard to clean up his act for some periods of time.”

Amid the gloom, glimmers of hope. Lynott secretly cut “Out in the Fields” with Gary Moore for £5,000 from Ten Records, bypassing management. Rumors of Thin Lizzy reunions swirled—Gorham discussed it during his Kew visit but saw Lynott’s deterioration: “Outwardly I’m going, ‘That’s a great idea’, but inwardly I’m looking at Phil thinking, ‘There’s no way in hell that he’s ready to be on the road at all’.” A solo deal with Polydor (£50k advance for two albums) sparked excitement. Sessions with Huey Lewis in San Francisco were planned, producer Tom Dowd lined up. But passport woes delayed Lynott; he arrived eight days late, unwell. “He was okay. He was clean. He was good. I insisted on that,” Lewis said. They nearly finished “Still Alive” and “Can’t Get Away,” with Lynott stretching his vocals back to classic ranges. “For about three or four years, he hadn’t sung in The Boys Are Back In Town or Jailbreak range,” Lewis noted. Lynott left early, tracks incomplete.

By late 1985, Grand Slam imploded. Stanway rejoined Magnum for stability: “I don’t want it to sound like I was deserting him. You have to make sensible decisions in your life.” Archer suspected the solo deal excluded him. In a December TV interview with Dante Bonutto, Lynott looked “a little bit yellow and… down.” He discussed ambitions—guests like Downey, Sykes, Moore; balancing hard rock and ballads. “The minute I went solo, people started to offer me deals,” he said. “Maybe Grand Slam suffered the backlash from Thin Lizzy fans.” Bonutto reflected: “He was struggling. He wasn’t getting the response that you would have thought that someone of his reputation would have got. It was very surprising… because if Phil had survived that period, he would be one of the biggest stars in rock now making records with Bono and Bon Jovi.”

Christmas Day 1985 brought the end. Lynott collapsed in his Kew bathroom, slipping out of the bath. Caroline drove him to Clouds House clinic, then Salisbury Infirmary diagnosed septicaemia. He fought for 11 days, speaking briefly to his mother, but pneumonia and heart failure—worsened by years of abuse—claimed him on January 4, 1986, at 36.

Lynott’s death shocked the rock world. “I was very shocked to hear of his death,” Bonutto said. “You never want to do the last interview with anybody, but I can’t be the only person who thinks that it could have been avoided.” Archer mourned: “It killed me that he wasn’t going to be there any more.” Today, on the 40th anniversary, Lynott’s legacy endures—Thin Lizzy’s riffs inspire Metallica, his lyrics echo in Irish rock. Statues in Dublin honor him; Grand Slam reformed in 2024 with Archer leading. But the “what if” lingers. If he’d survived, collaborating with Bono or Bon Jovi? Perhaps. Instead, his story warns of fame’s fragility. Phil Lynott didn’t just rock; he lived poetry, even in tragedy. The boys are back in town—forever in our playlists.