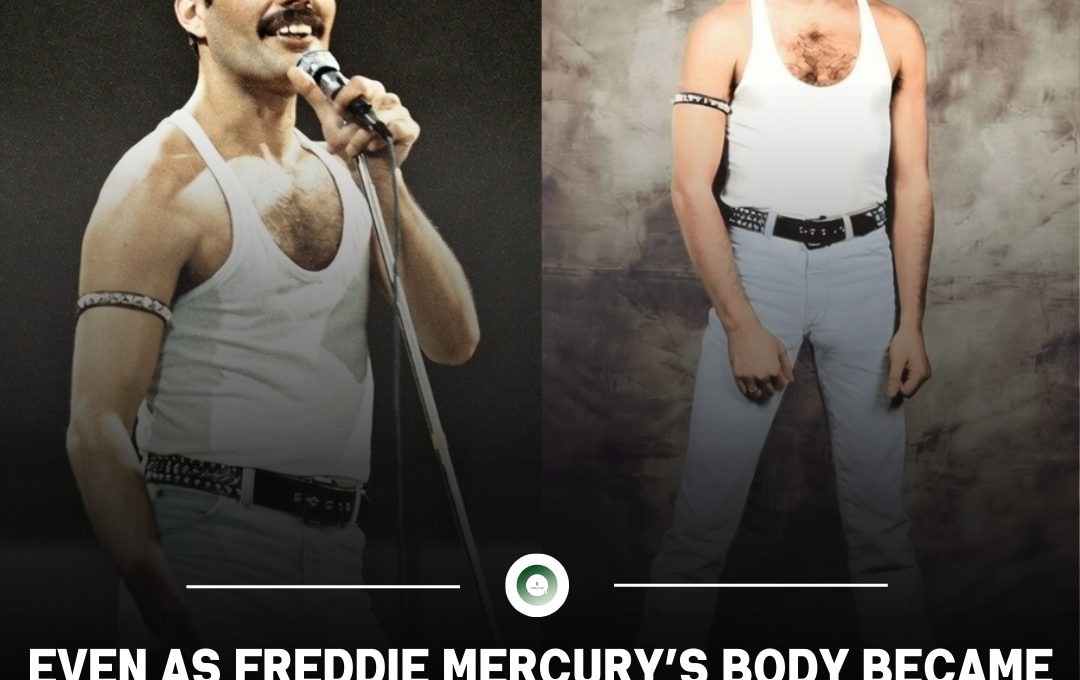

By the late 1980s, Freddie Mercury had already achieved the kind of permanence most artists spend entire careers pursuing. His voice had become structural — instantly recognizable, resistant to imitation, and deeply embedded in the cultural fabric that surrounded Queen’s music. But behind that permanence, something far less stable had begun to take shape. His body, once capable of sustaining the physical demands of global touring and extended studio work, was beginning to impose limits he could neither ignore nor reverse.

What followed was not a retreat.

It was a recalibration.

Freddie understood that the nature of his work was changing. The voice remained intact, but the conditions surrounding it had shifted. Recording sessions became more deliberate, more contained, and more intentional. The casual endurance that had once defined his presence in the studio was replaced by conservation. Energy was no longer something to expend freely. It was something to allocate carefully, reserved for the precise moments when it mattered most.

And when those moments arrived, he did not hold anything back.

Queen’s later recordings, particularly those created during the sessions for Innuendo and Made in Heaven, revealed a different kind of authority. The voice did not weaken. It intensified. Freddie’s performances carried a sharper clarity, a heightened sense of presence that reflected complete control over every note. The physical limitations surrounding him did not enter the recordings as compromise. They entered as pressure — and pressure, in his case, produced focus.

Songs like “The Show Must Go On” did not emerge from physical strength. They emerged from deliberate will. Brian May would later recall uncertainty about whether Freddie could physically deliver the song’s demands. The vocal range was punishing. The emotional weight was heavier still. But Freddie approached the microphone without adjustment. He did not lower the key. He did not ask for accommodation.

He recorded it as written.

The result did not sound like survival. It sounded like certainty.

What changed during these final years was not his voice, but his relationship to time. Recording was no longer routine. It became preservation. Each session existed with the awareness that it could not be repeated indefinitely. That awareness did not introduce hesitation. It introduced precision. Freddie did not use the studio to escape his condition. He used it to define himself independently from it.

There is a difference between endurance and authorship. Endurance accepts limitation. Authorship reshapes it. Freddie Mercury did not deny the reality of his physical decline. He reorganized his work around it, ensuring that what remained under his control — his voice, his interpretation, his presence — continued to operate without compromise.

The body introduced boundaries.

The voice refused to recognize them.