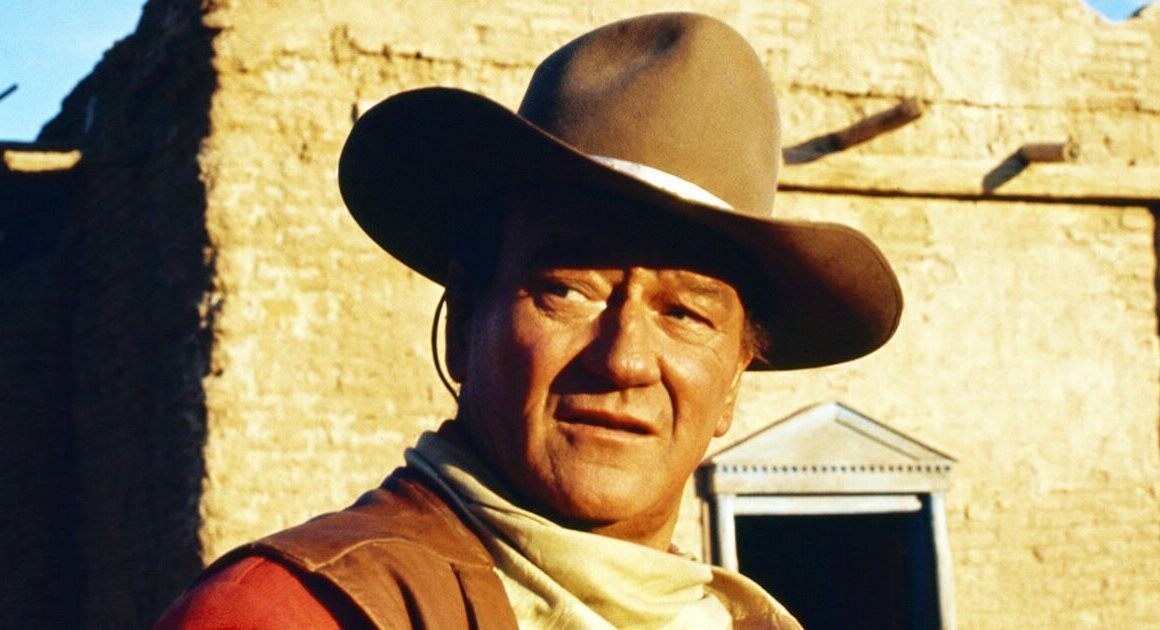

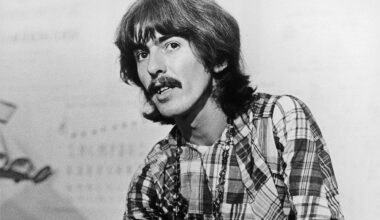

When Clint Eastwood traded his saddle on TV’s Rawhide for the dusty, lawless landscapes of Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns, one man watched with growing unease—John Wayne.

By the mid-1960s, Wayne had already spent decades as the face of the American Western. Films like The Alamo and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance had cemented his legacy, built on tales of honor, clear-cut heroes, and the pioneering spirit. But suddenly, the genre that had made him an icon was being rewritten, and Wayne didn’t like what he was seeing.

Eastwood’s arrival in 1967 with A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly shook the foundation of the Western genre. These weren’t Wayne’s frontier tales of noble cowboys and black-hat villains. Leone’s films were brutal, cynical, and morally ambiguous—everyone, from outlaws to sheriffs, had blood on their hands. The West wasn’t a land of heroes anymore; it was a savage, lawless world where survival meant getting your hands dirty.

Wayne, a staunch believer in the romanticized vision of the Old West, wasn’t impressed. In a rare candid moment in the late ’60s, he admitted his frustration:

“I was getting anxious because there was this young guy called Clint Eastwood making westerns in Italy and having tremendous success with them. All of a sudden, the studios all wanted Eastwood to come and make westerns for them, but they were not the kind of westerns I’d been making. They were tough and bleak.”

Wayne wasn’t just concerned—he was bewildered. Watching the rise of Eastwood’s gritty antiheroes, he reportedly asked, “I don’t get it. What do people see in these films?”

But nothing set Wayne off more than Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter (1973). The film, Eastwood’s second as a director, was a ghostly, violent tale about vengeance and corruption. To Wayne, it was a complete rejection of the values he believed the West—and America—stood for. So appalled was he that he personally wrote Eastwood a letter, criticizing the film for its portrayal of Western pioneers, stating it failed to “accurately represent the spirit of the people who made America great.”

Eastwood, unfazed, later reflected on Wayne’s reaction:

“I realized that there’s two different generations, and he wouldn’t understand what I was doing. High Plains Drifter was meant to be a fable; it wasn’t meant to show the hours of pioneering drudgery. It wasn’t supposed to be anything about settling the West.”

Hoping to bridge the gap, Eastwood later sent Wayne a script for a film called The Hostiles, envisioning the two Western legends finally sharing the screen. But Wayne refused to even read it, rejecting the idea outright. It was clear—this was a showdown that would never happen.

In the end, Wayne’s only brush with Eastwood’s world came through Don Siegel, the director of Dirty Harry, who helmed Wayne’s final film, The Shootist. Unsurprisingly, Wayne clashed with Siegel throughout the shoot, disagreeing with nearly every creative decision. Siegel, never one to back down, quipped to a local newspaper: “Wayne is supposed to eat directors for breakfast, but if he tries to eat me, he’ll get indigestion.”

Looking back, it’s easy to see why Wayne felt threatened. As biographer Scott Eyman put it, Wayne was deeply uneasy about the “drift toward nihilism” in Hollywood, and Eastwood’s rise signaled a changing of the guard. The Western was no longer about simple morality tales—it had become a reflection of a world where good and evil weren’t so easily defined.

Wayne’s era was ending, and Eastwood’s was just beginning. The cowboy had ridden into the sunset, but a new kind of gunslinger was taking his place—one who wasn’t afraid to get his boots a little dirty.