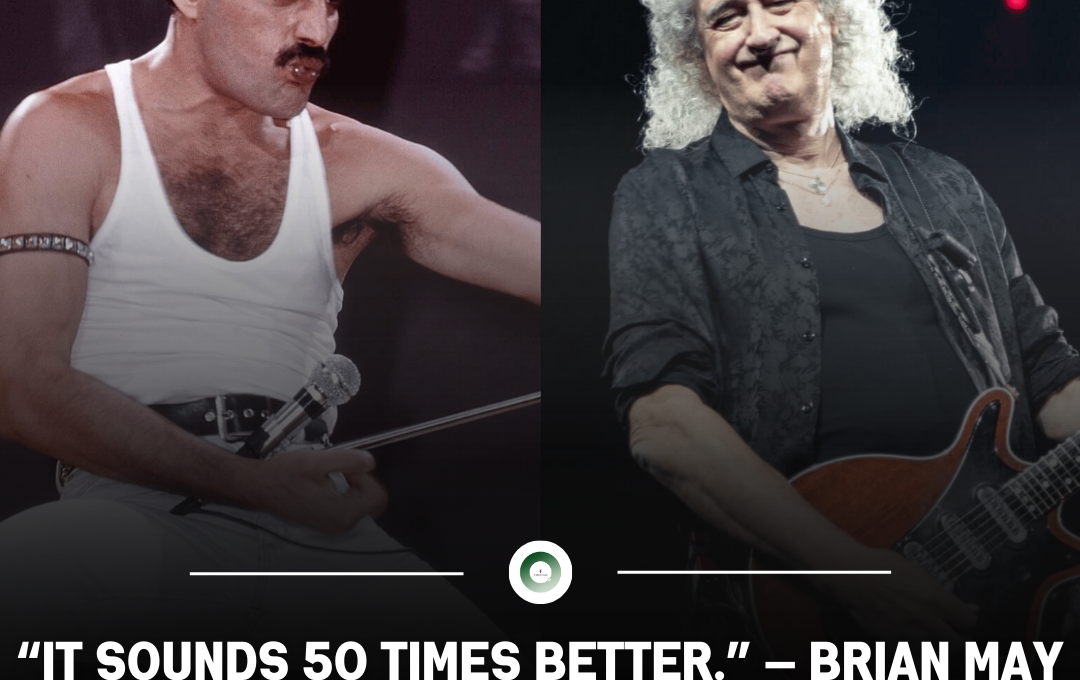

LONDON — When Brian May walked out of Abbey Road Studios with a quiet smile and a promise that sounded almost impossible, it instantly sent a ripple through the music world. The Queen guitarist claims his long-awaited Dolby Atmos rebuild of Queen II will sound “50 times better” than the original 1974 release.

For devoted fans and audiophiles, that statement doesn’t feel like marketing. It feels like a challenge—to everything they thought they knew about the album.

Because this isn’t a remaster. It’s a resurrection.

Not a Remaster — A Reconstruction From the Ground Up

Brian May has made one thing unmistakably clear: this project goes far beyond polishing old recordings. Instead of enhancing the finished stereo mix, the production team has returned to the original multi-track tapes—the raw, untouched foundations of Queen’s sound.

Every individual element has been isolated. Freddie Mercury’s vocals. May’s layered guitar orchestras. Roger Taylor’s explosive drums. John Deacon’s grounding bass lines. All of it has been rebuilt piece by piece.

The result isn’t simply improved clarity. It’s immersion.

In Dolby Atmos, listeners won’t just hear Queen II. They’ll exist inside it.

May has already teased parts of the opening instrumental, “Procession,” describing the new mix as placing fans directly inside his famous guitar arrangements. In 1974, Queen pushed analog tape to its absolute limits, stacking overdub upon overdub until the technology itself struggled to contain their ambition.

Now, modern spatial audio removes those limits.

For the first time, the music can breathe exactly as Queen imagined it.

Freddie Mercury’s Voice, Unbound by Time

Perhaps the most astonishing transformation lies in Freddie Mercury’s voice.

In the original stereo mix, his vocals were locked into fixed channels, constrained by the physical limitations of the era. In Dolby Atmos, those restrictions disappear. Mercury’s voice can move freely within a three-dimensional space.

The effect is deeply unsettling—in the best possible way.

Harmonies that once blended now separate and surround the listener. Subtle textures buried beneath layers of tape compression suddenly emerge. Call-and-response passages feel alive, unfolding around you rather than from a distance.

Tracks like “The March of the Black Queen,” long considered one of the band’s most complex compositions, reveal entirely new dimensions. Its unpredictable shifts, dramatic structure, and operatic ambition—already revolutionary in 1974—now feel even more daring.

It doesn’t sound restored.

It sounds reborn.

From Cult Classic to Definitive Statement

When Queen II first arrived, it wasn’t an instant commercial juggernaut. Its theatrical intensity and conceptual structure divided listeners. The album’s symbolic “White Side” and “Black Side” reflected two creative worlds—Brian May’s disciplined compositions and Freddie Mercury’s darker, fantastical vision.

But over time, the album transformed from curiosity into cornerstone.

It gave Queen their first UK Top 10 hit with “Seven Seas of Rhye.” Its iconic diamond formation cover photo, captured by Mick Rock, later became one of the most recognizable images in rock history—immortalized again in the Bohemian Rhapsody music video.

What once felt experimental now feels foundational.

And technology may finally elevate it to its full, intended power.

Hidden Recordings and the Secrets of the Past

The upcoming 2026 box set promises even more revelations.

Among the most anticipated additions is “Not for Sale (Polar Bear),” a long-rumored outtake from the original sessions that Brian May recently previewed. The expanded release is expected to include alternate takes, BBC recordings, and rare live performances—offering a deeper glimpse into Queen’s creative peak.

The release strategy mirrors the band’s recent expanded reissue of Queen I, with deluxe multi-disc editions, Blu-ray Atmos mixes, and collector vinyl pressings.

For longtime fans, this isn’t just nostalgia.

It’s discovery.

Technology Finally Catches Up to Queen’s Vision

There’s something profoundly poetic about this moment.

In 1974, Queen stretched studio technology beyond its limits, forcing analog tape to contain ideas far larger than the tools allowed. Now, more than fifty years later, technology has evolved enough to finally match their imagination.

Brian May’s excitement doesn’t come from revisiting the past.

It comes from finally revealing it.

If his promise holds true, Queen II won’t simply sound cleaner, sharper, or more modern.

It will sound the way it was always meant to sound.

Not as a relic of its era.

But as something timeless.

Because as Brian May is now suggesting—with quiet confidence and undeniable conviction—

You may love Queen II. But you’ve never truly heard it.