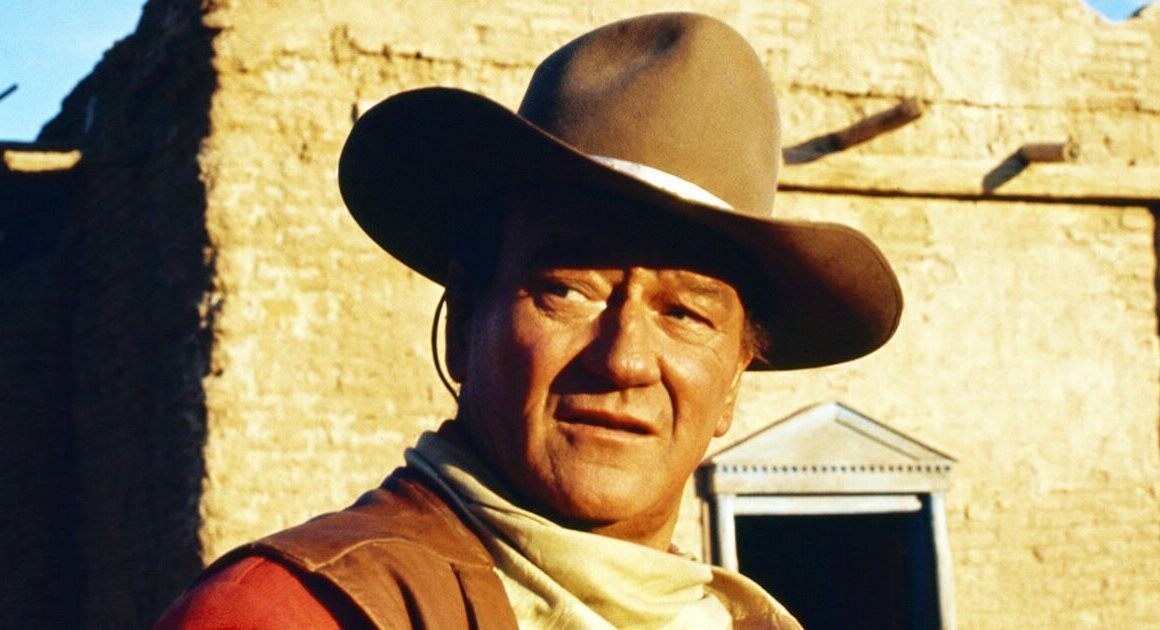

John Wayne was the first to acknowledge that not all of his films were cinematic masterpieces. While classics like Stagecoach and The Searchers cemented his legacy, there were also forgettable entries like Hellfighters and The Conqueror. Given that he racked up nearly 200 acting credits before his passing in 1979, it’s no surprise that a few were misfires.

Among them, Wayne himself regarded Jet Pilot (1957) as his worst film. Bankrolled by the eccentric Howard Hughes, the Cold War-era aviation flick became more of an aircraft showcase than a compelling narrative. Hughes’ obsessive perfectionism kept the film in post-production limbo for years before it finally saw release—long past its relevance.

Wayne’s longtime collaborator, director Howard Hawks, might have pointed to a different misstep. Hawks, a cinematic legend in his own right, directed a variety of genre-defining films, from screwball comedies like Bringing Up Baby and His Girl Friday to film noirs such as The Big Sleep. He teamed up with Wayne for five films: Red River (1948), Rio Bravo (1959), Hatari! (1962), El Dorado (1966), and Rio Lobo (1970). Among these, one is a revered classic, while another is widely considered a disappointment—despite both sharing similar storylines.

The masterpiece is Rio Bravo, a gripping Western where Wayne portrays a sheriff who, alongside an aging deputy, a washed-up drunk, and a young gunfighter, defends his town against outlaws intent on springing a murderer from jail. The film’s elegant storytelling, strong performances, and unpretentious execution make it a standout in Wayne’s career and one of Hawks’ finest works.

Rio Lobo, on the other hand, fails to capture the same magic. Released just over a decade later, it treads overly familiar ground, revisiting themes and scenarios from Rio Bravo and El Dorado. This time, Wayne plays a Union Army colonel hunting down Confederate raiders who stole a gold shipment. Post-war, he reconnects with former adversaries, leading to yet another variation of the siege-at-the-sheriff’s-office scenario. The problem? Audiences in 1970 had little interest in seeing the same formula rehashed yet again, especially with Hollywood in the midst of a creative revolution that favored grittier, more modern storytelling.

Financially, the film floundered, failing to recoup its $6 million budget. Hawks himself admitted disappointment, though his reasoning had more to do with the casting than the tired plot. In a 1975 interview, he lamented, “Rio Lobo was a mistake because they didn’t have the money. We needed two good people. Otherwise, my story wasn’t any good. I saved the story and just wrote that damn piece of junk and made it.”

Would the film have fared better with a major co-star like Robert Redford or Warren Beatty? Perhaps. But its fundamental flaw wasn’t the lack of a strong supporting actor—it was its stale sense of déjà vu. By 1970, audiences craved innovation, not a secondhand version of Wayne’s greatest hits. Rio Lobo ultimately served as a reminder that even legends can overplay their hand.